hōiekko-vezet lo̱hhaumkuive.

I can only give a snowstorm.

A Tesyāmpa saying meaning ‘you want proof, I can only

give you evidence’. Comes from the poem ‘Winter‘.

- Oldtale (rōamtse̱ti)

- Phonetics

- The World Divided

- Overview

- Charts (pronouns, determiners, suffixes)

- History

- Writing System

- A Bit of Vocabulary

- Winter (kāx)

Tesyāmpa (literally ‘language’) is my most recent conlang. The seed idea was just to design ‘logical logographs’, which term I was using very loosely to mean something similar in format to Chinese characters, but more regular and more straightforwardly interpretable. And I did design those, in the end! But in the process I had to decide things about the language these characters were representing, and of course I had to know what the logographs meant… and an analytic language like Mandarin kind of seemed like not enough of a stretch, so I made some affixes… and so on….

Before too long, I had divided the world into 78 categories, and the language had expanded along with the writing system as I went. The bare bones of an imaginary culture also sprang up, directly driven by the development of the language. (This culture is probably but not definitely composed of humans; for now, the species that speaks Tesyāmpa is referred to below as ‘selfspecies’.) The writing system started out with a vaguely Mayan style; the final format of the characters has some resemblance to Chinese; beyond that, Tesyāmpa isn’t based on anything in particular.

As a language, Tesyāmpa is concerned with:

animacy and politeness;

evidentiality, possibility/potential, uncertainty, and questions;

direction/location, motion, movement in time, and change;

effect/result; patterns and habits.

Tesyāmpa is relatively unconcerned with:

number; sex-based gender; the past;

desires/goals, intention, method, or degree of ease;

cause, completion, permanence, duration, or definiteness.

Oldtale

rōamtse̱ti

tso̱ttotak yāuli kka̱mai lātsek re̱itsalau – pi̱a – tūn.

hōifuatsʊt āulyasʊstu lātsekau va̱kteive – tau – chʊ̱lataiayatsʊt va̱kte re̱i. te̱in hūqa kka̱mpei.

te̱iatsʊt le̱lo āulyasʊstu le̱uhio o̱utum lātsek, tto̱ai vāu a̱rvesasʊ re̱ikkoi tsōɫtak.

re̱ikkoi xōinitaiaye lātsek.

rōa-m-tse̱ti

tale-heard.reported-be.old

tso̱tto-tak yāuli kka̱m-ai lātsek re̱i-tsal-au – pi̱a – tūn.

past-in be.far run-3P.M.M.PST crocodile every-place-LOC, mountain, tree.

hōifu-ats-ʊt āulyasʊs-tu lātsek-au va̱kte-ive – tau – chʊ̱la-taia-yats-ʊt va̱kte re̱i.

gift-PST-3P.S.S god-PL crocodile-LOC tooth-INST, but, cost-ful.S-PST-3P.S.S tooth all.

te̱i-n hūqa kka̱m-pei.

not-3P.M.FAR.M.PRES continue run-act.

te̱i-ats-ʊt le̱lo āulyasʊs-tu le̱uhi-o o̱u-tum lātsek,

not-PST-3P.S.S know god-PL be.lazy-3P.M.S.PRES such-extent crocodile,

tto̱-ai vāu a̱r-ves-asʊ re̱i-kkoi tsōɫ-tak.

anyway-3P.M.M.PST want attach-here-3P.M.I.FUT(INDIC) all-time river-in.

re̱i-kkoi xōini-taia-ye lātsek.

all-time trick-ful-3P.M.PROX.M.PRES crocodile.

Oldtale

Long ago, crocodile ran everyplace. Mountains, trees.

Gods gifted crocodile teeth, but each tooth cost. No more running.

Gods didn’t know crocodile so lazy, wanted stay in river forever anyway.

Crocodile always tricksy.

Phonetics

Phonemes

/p/, /pp/; /t/, /tt/; /k/, /kk/; /q/; /s/, /f/,/ /z/; /m/; /n,/ /ng/, /ny/; /v/; /y/; /ts/, /x/, /ch/; /h/, /r/, /hh/; /l/, /ɫ/, /ly/

/a/, /ai/, /au/; /e/, /ei/, /eu/; /o/, /oi/, /ou/; /i/; /u/; /ʊ/

Pronunciation

/pp/, /tt/, and /kk/ are aspirated; /hh/ is IPA [χ]; /q/ is IPA [q]; /ɫ/ is a very dark l; /x/ is a general ‘sh’ sound; /v/ sounds like a cross between v and w; /r/ sounds close to rh or hr. For vowels, /a/ usually sounds like ah; /e/ is e/ɛ; /i/ is i/ɪ; /ʊ/ is roughly the vowel in ‘good’; /o/ is o/aw/ɔ. Syllables are (C)V(C).

Tone

I’m just dipping my toes into using tones, here. There are two tones, level high and low, not counting a neutral mid; generally one tone per ~word, on the first syllable (exception for some compounds); the syllable with tone is stressed, so that tone can be thought of as two different classes of stress/accent. In practice the low tone is sometimes the equivalent of Mandarin tone 4: that is, a sharp falling tone. The rest of the word adapts to this tonal stress.

Transliteration

For convenience, ‘ʊ’ can optionally be typed as ‘w’. Conveniently, when digraphs happen to be formed by consecutive consonants, they’re pronounced as that digraph! (A double /h/ would not become /hh/, but /h/ does not end syllables, so it doesn’t come up.) Tone/stress is not directly represented in Tesyāmpa’s writing system, but diacritics are used in transliteration: hīgh tōne and lo̱w to̱ne accents, or overlines and underlines.

The World Divided

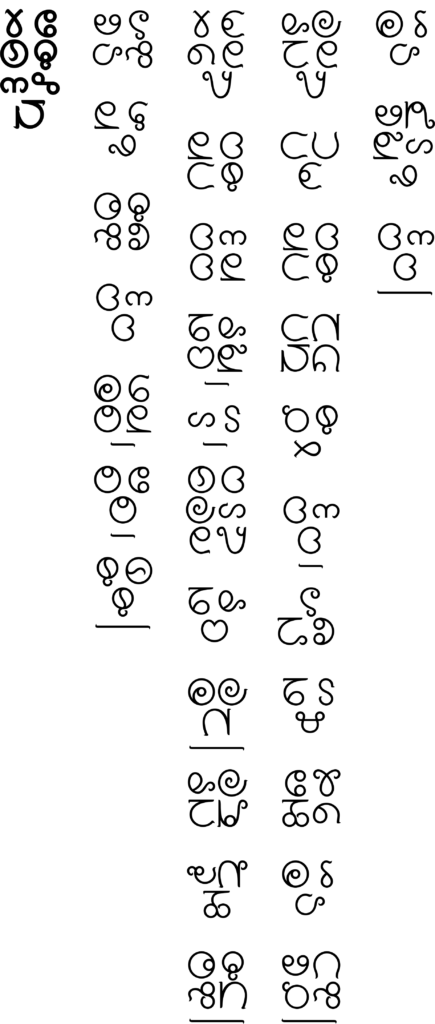

Tesyāmpa is written using 72 basic symbols, each with up to three readings depending on placement: as a determinative (semantic (meaning)), as a syllable (phonetic), and as a suffix (irregularly phonetic). This is a chart of the determinatives, which are the semantic categories that form the base of the writing system; the concept is roughly equivalent to Chinese radicals. Exactly one category applies to (almost) every word. They’re somewhat like noun classes, and somewhat like classifiers; but they’re not just for nouns and they’re not reflected in the standard pronunciation.

The phonetic (syllable) and suffix readings of the symbols are also listed; the *asterisk indicates the reading when a symbol is flipped (more details in the writing system section).

| Concept | Meanings | Anim. | Word | Syll. | Suff. | Sym. | Early Symbol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| flute | musical instruments, weakness (traditionally, wind instruments are the ‘weak’ class) | stately | āttal | a *ai | ya *ai |  |  |

| ghost | intangible/ spirit, far, away | mobile | e̱s | e *ei | e |  |  |

| shell | fungible things like money, flat in slices, options/ choice | inert | īx | i *i (new syl) | i |  |  |

| cave | cave/ underearth/ deep, low, darkness, hide/ secret | inert | o̱ttu | o *oi | o *oi |  |  |

| icicle | cold/ winter, stop in a cold (s) way (freeze) | stately | ūlyus | u *u (new syl) | u |  |  |

| snake | sickness/ corrode/ poison/ slowpain, defeat/ loss/ failure | mobile | ʊ̄s | ʊ – | ʊ |  |  |

| dog | helpful/ useful/ cooperative animals, walk/ go, work (action of) | mobile | ha̱k | ha *ahh | tak *takki |  |  |

| sun | heat/ summer, day, go in an energy way | stately | hēɫ | he *ehh | hel |  |  |

| globe | globe/ world/ everything, all, certain, decided | stately | hiqʊ̱mya | hi *ihh | a̱mya *_ma |  |  |

| face | face, discover/ opposite of secret | mobile | hō | ho *ohh | iha *ohh |  |  |

| songbird | sound (musical) | mobile | hūqle | hu *uhh | ^su |  |  |

| salt | salt/ extra/ soul/ spice, ha̱is | inert | hʊ̱la | hʊ *ʊhh | _sa |  |  |

| ear | perception, truth | stately | kāt | ka *ak | kas *kaski |  |  |

| wave | sound (roar), xāu | mobile | ke̱hh | ke *ek | kkas |  |  |

| door/gate | passthrough/ path, enter, leave/ exit, open, avoid/escape, unlikely/ improbable | inert | kīti | ki *ik | ki |  |  |

| anthill | social animals (nonselfspecies), many, societysystem, public | mobile | kko̱ | ko *ok | kkou |  |  |

| treetop | treetops/ movingplace, high, climb, constant windlike motion | mobile | kūzan | ku *uk | ku |  |  |

| jar | container/ inside/ category, empty, nothing, less, without | inert | kʊ̄ho | kʊ *ʊk | ^sʊt |  |  |

| crocodile | semiaquatic animals, terrible | mobile | lātsek | la *al | lya *ātsa |  |  |

| moon | celestial bodies, night, spherical, gods | stately | le̱ | le *el | _me *e̱l |  |  |

| fish | fish/ obligatory aquatic animals/ swimmers | mobile | līm | li *il | uli |  |  |

| boat | travel/ transport | stately | lōta | lo *oɫ | long |  |  |

| dusk/dawn | transitiontime, change, decide | stately | lu̱ko | lu *ul | lu *luki |  |  |

| incense | fragrance/ smoke/ steam/ cloud/ goodvapor, sleep/ dreams, slow | stately | lʊ̱q | lʊ *ʊɫ | _sʊ |  |  |

| stew | food, more, plenty, full, with | inert | ma̱ntul | ma *am | _ma *(a)m |  |  |

| tide | tide/ blood, circulation/ timecycle, rhythm, habit, strength in a tide sense | stately | mē | me *em | ē |  |  |

| frayed string/ end | measure, stop in a come-to-an-end (i) way, hair/ fur/ featherish stuff | inert | mi̱t | mi *im | set |  |  |

| driftwood | onwater/ float, shallow, seeming/ apparently, changeable, variable | inert | mōz | mo *om | mo |  |  |

| brick | buildingpieces, orthogonal/ rectilinear, flat on top | inert | mūnlyu | mu *um | ^sun *uma |  |  |

| shelf fungus | death/ end/ autumn, old, tired | stately | mʊ̱tti | mʊ *ʊm | _mʊt |  |  |

| sky / be blue-green | light/ color, light, clear | stately | nāng | na *an | yā *an |  |  |

| bread | intentionally made items (not too big), half (traditionally, bread is ‘half of a good meal’) | inert | nēkka | ne *en | ne |  |  |

| water | liquids | inert | nīqu | ni *in | ū *in |  |  |

| web | net/ caught/ tangled, join/ meld/ meet/ combine | inert | no̱stop | no *on | _sat |  |  |

| headwrap | cloth and clothes, presentation | inert | nūpsu | nu *un | sun *un |  |  |

| body | body parts, inherent part of something, clusterness | mobile | nʊ̄ma | nʊ *ʊn | ^sʊ |  |  |

| town/city | city / many people, bump/ jostle | mobile | pa̱r | pa *ap | ha |  |  |

| rhinoceros | dangerous animals (bigger than bug), fight, confront, oppose | mobile | pēlye | pe *ep | pei |  |  |

| mountain | high/ outside place, location, direction, wide, big | stately | pi̱a | pi *ip | sin |  |  |

| lightning | lightning (later electricity), sudden, clarity | mobile | po̱ | po *op | ekko |  |  |

| drum | drum/ beat/ repetition, strength in a drum sense, beat/ count/ time, numbers | stately | pu̱nye | pu *up | nye *nyeki |  |  |

| grass | spready/ short plants, agriculture, compliance, inclination/ probable, horizontal | stately | pʊ̄voi | pʊ *ʊp | oiki |  |  |

| rake (three-pronged) | nonweapon tools, triple, use | inert | qāzes | qa(ka) *aq(ak) | ^se |  |  |

| kelp | underwater, deep, unknown | stately | qōka | qo *oq | ^sa |  |  |

| baby | baby things/ beings/ plants, young | mobile | qūqu | qu *uq | uqu |  |  |

| roof | house/ shelter/ lowplace, inside, narrow, closed | inert | qʊ̄k | qʊ *ʊq | ^ʊt |  |  |

| clan/tribe/ family | family/ clan/ tribe, close, near, toward | mobile | sāttekke | sa *as | sa *(a)f |  |  |

| octopus | octopus, eight, distributed, pretend/ mimic/ copy/ practice, clever, transform/ adapt | mobile | se̱le | se *es | se |  |  |

| tongue | taste / emotive opinion, qualia, emotions | mobile | zi̱ts | si *is | ezi *isi |  |  |

| tortoise | safety/ security, stop in a tortoise (m) way | mobile | so̱tu | so *os | _sau |  |  |

| head | thinking/ mind/ knowledge | mobile | sūt | su *us | su |  |  |

| hand | hand, reach, earn/ gain, to effect, pairness | mobile | sʊ̱ | sʊ *ʊs | sʊ |  |  |

| earth | earth/ dirt/ ground, massstuff, lumpy, inner flesh | inert | ta̱mna | ta *at | taia |  |  |

| rope | long stringy stuff, long | inert | tte̱s | te *et | tte *et |  |  |

| writing | writing/ representation/ standin/ symbols | stately | tīhom | ti *it | ti |  |  |

| this | pronoun/ demonstrative, specifier/ identity | stately | tō | to *ot | toif |  |  |

| tree | vertical/ upright, strength/ endurance in a tree way | stately | tūn | tu *ut | tu *ūn |  |  |

| thornbush | injure/ damage/ fastpain, spiky | mobile | tʊ̱pait | tʊ *ʊt | _sai *ʊt |  |  |

| spear | weapons, force/ coercion/ threat | inert | tsa̱k | tsa *ats | atsa *ats |  |  |

| bird (flying) | birds/ flight, play/ fun | mobile | tsēts | tse *ets | āts |  |  |

| rain | weather (precipitation, etc.), relief, largescale more-or-less natural phenomena | mobile | tsīx | tsi *its | yax |  |  |

| pangolin | peacefully coexisting animals, midsize, singleness | mobile | xōs | tso *ots | xo |  |  |

| stone | stoneish stuff, terrain, be/ stay/ remain/ constant, embody | inert | tsu̱ | tsu *uts | atsu *achu |  |  |

| mouth | speech/ language, systems | mobile | tsʊ̄ | tsʊ *ʊts | sʊt |  |  |

| knife | split/ slice/ cut/ separate, distinguish, different/ other | inert | va̱ | va *au | a̱tsam *au |  |  |

| king/chief | important specific person, honor, respect | mobile | vētyan | ve *eu | (i)ve |  |  |

| wood | woodish stuff, roughtexture | inert | vīo | vi – | iu *(v)ive |  |  |

| wind | air/ freshness, fast | mobile | vō | vo *ou | oskki |  |  |

| flower | beauty/ aesthetics/ art | stately | vūtsu | vu – | ātsu |  |  |

| shield | metal stuff, guarding/ armor/ protection, smooth | inert | vʊ̱yuk | vʊ – | _mu *yeu |  |  |

| bogslime | miasma/ badvapor/ dirt/ filth/ foulness/ stink, nightmare/ mindgunk | stately | ōcha | – | (high tone) |  |  |

| winged lion (has cool horns, etc.) | myth/ greatness/ extraordinariness, magnificence, win/ triumph/ success | mobile | o̱ukka | – | (low tone) |  |  |

Six (and only six!) of the determinatives can be flipped, which in this context more-or-less adds a diminutive to the original concept. This makes six additional valid semantic categories:

| Concept | Meanings | Anim. | Word | Sym. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| beetle (flipped anthill) | little buggish animals, germs, small | mobile | fēi |  |

| bark (flipped wood) | bark/ skin/ outerlayer, brittle/ breakable/ dry/ fragile, fake/ false | inert | i̱nto |  |

| adult person (flipped king) | selfspecies, personal | mobile | ko̱me |  |

| sprout/sapling (flipped grass) | life/ born/ start/ new/ spring, new, resilient/ wet | stately | qʊ̄tsou |  |

| fire (flipped sun) | moving unalive things (not water) | mobile | sāhux |  |

| river (flipped wind) | moving unalive things (water), recklessness and caution | mobile | tsōɫ |  |

Overview

(Or a slightly more detailed overview.)

Animacy

Animacy is important in Tesyāmpa! There are three classes of animacy based on motion either physically or in the brain: mobile, stately, inert. Stately includes not only gradual motion over time, but also potential. All words except for conjunctions have an animacy. Nouns don’t reflect their animacy in their pronunciation or representation; a word’s determinative tends to match its animacy, but that’s not at all required. Some verbs have different ‘versions’ depending on animacy, and using the wrong one (not matching the animacy of the subject of the verb) is ungrammatical (although can occasionally be intentionally done for wordplay or poetic effect).

Word Order

Pretty flexible in general. Word order can indicate importance, important coming first; often this takes the form of mobile jumping ahead of inert. Most commonly VSO, object-oblique, conjugatedbaseverb-topverb; noun-determiner-stativeadj-adverb, verb-adverb. Adverbs can move around. Noun-stativeadj order is set.

Copula

For 1-to-1 identity, the relevant things use the equals (or not-equals) verb like a regular verb. For descriptive or existence, verbify an adjective or noun by conjugating it; for example, ‘there exists a dog’ is simply ‘dog-3P.M.S’ (ha̱ko).

Pronouns

Optional number marking, with plural form regular; exceptions for both for 1P. 2P is used only for informal/familiar. Polite speech circumlocutes – uses respectful title/descriptor, combines with vocative, uses 3P conjugations. Pronouns can be dropped when the verb conjugation or context makes the meaning clear, but they might still be used for emphasis, brief answers to questions, etc. The mobile pronouns (1P, 2P, 3P) typically form the possessive on a noun by compounding after it; for example, ‘my shell’ is ‘shell-I’, ‘īx-nu’. Phrasing it as ‘īx nūyu’ means closer to ‘shell of mine’.

Demonstratives

Optional number marking, plural form regular. When plural is specified, demonstrative is marked, not noun. 3-way proximity distinction. Used as 3P inert pronouns and also sometimes a definite article, essentially (there’s no indefinite article). When used with/as pronouns, they signify proximate/obviate/far rather than near/medial/distal – a bit more metaphorical.

Quantification

Optional number marking, singulative (one) or plural or other numbers to specify. Plural is never used when a number is given. Count/noncount noun distinction is unmarked – all nouns are treated as noncount as much as possible. All/every, none, and specific numbers are inert qualities; other amounts are generally stately. Numbers are base 12 and classified under drum, with a few specific exceptions. Long numbers are written as compound words.

Negation

There are a couple negative verbs, which conjugate regularly; any other verb follows them in the infinitive. Double negation with indefinite pronouns like nothing or none or nobody. ‘I don’t walk every day’ means I probably walk but not every day (as in English); to distinguish, the adverbial phrase can be moved around: ‘every day I don’t walk.’

Questions

There’s a polar ‘yes/no?’ that goes first if modifying a whole sentence and otherwise attaches to a specific word. ‘What’ attaches to certain words (not always completely regularly) to form who, where, etc. Any form of question tends to be bumped up in word order. Intonation alone is insufficient for forming a question. No specific interrogative punctuation, just the comma/pause or sentence ender.

Imperative

The use of e̱l as an imperative is limited; it wouldn’t even be used from a boss to an employee. Some of its uses are: from parents/adults to (usually their own) kids, if they’re impatient or being stern (highly variable); between friends – the effect in this case is to (often in a teasing/joking manner) express a great desire for them to do the thing; to someone who you feel has wronged you / done you a dishonor and now must act to ameliorate that; when complaining at a malfunctioning computer; as commands to a trained animal; to command slaves; when yelling at someone to stop so they don’t fall off a cliff; for emphasis in a royal decree, as a supplement to the future indicative. Future indicative can be used generally when compliance is expected, as in parent-child or boss-employee, but future possible (plus context and circumlocution) is the politest form.

Evidentials

There are four evidential markers: one for direct perception, one for deduced from evidence, one for reported/secondhand/thirdhand, and one for assumed as prior/given. Strictly speaking, they’re always optional, but they’re generally used in most transmission of information, and in the title of stories or anecdotes.

Suffixes

Tesyāmpa has 96 ‘official’ suffixes, with agglutination and a bit of fusion. (This number is somewhat arbitrary, as is the lack of prefixes: there are a few more words that can essentially affix to other words, but they’re written as compounds.) The suffix that’s first in attachment order combines with the base word; others add on, similarly to compounding. An epenthetic y or a is added (in pronunciation, not in representation) when needed to differentiate syllables; but when suffixes start with i or u (except for a couple verb endings), they diphthong with the base word when possible instead of taking y.

Compounding

Simple smushing of base words, no internal conjugation. The part of speech most commonly matches the first component; exception in that determiner-noun results in an adverb. Tone likely only stays on the first word, but can do other things. Established compounds are usually (but not always) written as a single character. Some verbs can follow a main verb by compounding to it, modifying the main verb: for example, ‘tōno’ (repeat) can be added to ‘kkūzya’ (you build) to make ‘kkūz-tōnoya’ (you rebuild).

Verb Animacy

Base verbs are morphologically divided by animacy (exceptions for compounds and verbs that are direct conjugations of a noun).

Base verbs starting with u̱: inert-only.

Base verbs starting with kk, tt, pp, or ā (including āu and āi): mobile-only.

Base verbs starting with k, t, p, or any vowel other than u̱ or ā: stately-only.

Base verbs starting with any other consonant: either mobile or stately.

Most verbs have only a single version with a fixed animacy, and any noun can use it when called for. Some verbs have fixed ‘versions’, and a noun subject must use the verb version that agrees with its animacy. The grouping is either M/S (with I nouns also using the S version) or M/S/I. The M/S distinction need not be distinguishable; that is, M and S can share the same base and only differ in which odd-case conjugation they take. Determinatives may or may not differ between versions.

Eight particular verbs are distinguished in animacy by having multiple different forms – these are still classed as versions of the ‘same’ verb, which means that subject-verb animacies must agree. These verbs are: have(m/s/i), stop(m/s/i); go(m/s), come/arrive(m/s), continue(m/s); say (hold meaning/ information)(m/(s-i)), need(m/(s-i)), help(m/(s-i)).

Conjugation

The floating tones of verb endings affect the final syllable of the base word; if it was a one-syllable word that already carried that tone, it reduplicates the initial (C)V of that word so that, for example, qōu (swim) would become qoqōu (swimming, as in the phrase ‘if the moon is swimming’). Compound tenses are shown by kind of directly conjugating consecutive verbs. Pluralizing a verb means it’s done more than once (in quick succession or at the same time); when there’s an implied object, it generally means the object is plural.

Conjugation is a bit complicated in that it depends not only on the subject, but also on the animacy of the verb itself; ‘I run’ (mobile verb) takes a different ending than ‘I float’ (stately verb), and categories combine in various tenses and aspects. But hey, at least conjugation isn’t affected by the object of the verb, and the total number of unique verb endings (that are affected by tense and person) is only 48! It could be a lot worse.

Transitivity

The transitive is rarer than in English, and no verbs are obligatorily transitive. Transitivity plays out differently depending on animacy. Stately verbs are always considered intransitive and generally use the locative to directly affect an object; inert verbs are intransitive and cannot directly affect an object. With mobile verbs, if the subject is more animate than the object, the relation is directly transitive and uses the accusative; if the subject is less animate than the object, the relation is intransitive, and must use the locative. Inert-inert and stately-stately use the locative. Mobile-mobile generally uses the locative, but can use the accusative in roughly the same sort of conditions as the imperative, or also when the action itself is harsh and direct (such as ‘bites dog me-ACC’).

Passive

‘Verb-act-have’ serves as a passive. Instead of ‘I was bitten (by the dog)’: ‘bite-act-had I (dog-via)’. Instead of ‘the door is pounded (by me)’: ‘pound-act-has door (I-via)’.

Parts of Speech

Divides pretty neatly into verbs (v), nouns (n), determiners (d), and adverbs (a). Determiners (distinct from determinatives!) can generally also serve as nouns. Interjections can fill any of the four slots.

Adjectives (the absence of)

There are no adjectives as base words, if not counting determiners. Adjectives are formed by stative verbs, and conjugate as such (nearly): basically, if a verb follows a noun, it functions as an adjective. ‘House (that) is-being-red’ means ‘red house’. Verbs in this role generally conjugate in the simple present, and the ending drops completely for 3P-inert.

Adverbs

There are a few adverbs as base words, and more formed from compounds or suffixes. The function of other adverbs can be served by stand-alone or leading verbs, or postverb compounds, or nouns plus the instrumental suffix, or verbs plus the conjunction ‘while’ (yāits). Adverb-equivalents are generally not as common as in English.

Charts

Pronouns

| 1P singular, I | nū |

| 1P plural, we (inclusive and excl.) | yēn |

| 2P (*explicitly plural) | ta̱ (*ta̱tu) |

| 3P M-proximate, they (*plur.) | kē (*kētu) |

| 3P M-obviate, they (*plur.) | xūn (*xūntu) |

| 3P M-far, they (*plur.) | pa̱i (*pa̱itu) |

| 3P M high-status, they (*plur) | kē-tez(*tu); xūn-tez(*tu); pa̱i-tez(*tu) |

| 3P S, it/they: prox, obv, far (*plur.) | lo̱, lo̱za, lo̱pu (*lo̱tu, *lo̱zatu, *lo̱putu) |

| 3P I, it/they: prox, obv, far | tō, zā, pu̱ |

Demonstratives

| this, these (m) | tēz (tēztu) |

| this, these (s/i) (*plur.) | tō (*tōtu) |

| that, those medial (*plur.) | zā (*zātu) |

| that, those distal (*plur.) | pu̱ (*pu̱tu) |

| what/which (*plur.) | ēx (*ēxtu) |

| none | ye̱f |

| all/every | re̱i |

| some (unspecified) | sīu |

| other/else | pēt |

Numbers

| zero | ye̱f | jar |

| one | kka̱ | pangolin |

| two | sa̱i | hand |

| three | nō | rake |

| four | ku̱m | drum |

| five | xē | drum |

| six | po̱i | drum |

| seven | zʊ̄ɫ | drum |

| eight | la̱u | octopus |

| nine | tsī | drum |

| ten | mēit | drum |

| eleven | hū | drum |

| twelve | a̱pa | drum |

| thirteen | apa-ka̱ | drum-pangolin |

| twenty-seven | saipa-nō | drum-rake |

| forty-eight | ku̱mpa | drum |

| eighty-four | zʊ̄ɫpa | drum |

| one hundred twenty-four | meipa-ku̱m | drum-drum |

| one hundred forty-four | āngka | drum |

| one hundred forty-five | āngka-ka̱ | drum-pangolin |

| one hundred eighty-six | āngka-nopa-po̱i | drum-drum-drum |

| five hundred seventy-seven | ku̱ngka-ka̱ | drum-pangolin |

| one thousand and eight | zʊ̄ngka | drum |

Conjugation

Here is a conjugation chart! It can seem either pointlessly overcomplicated or kind of minimal depending on how I frame it, but I think it’s pretty!

This chart applies to almost any verb. In addition to the categories shown, stately and inert verbs can be conjugated as though they were mobile as a way of denoting particular respect for a (mobile) subject.

The letter after the dash refers to the animacy of the verb; ‘3S–M’ means a stately third-person, singular or plural, that is the subject of a mobile verb. The ^ and _ indicate a high or low tone that affects the previous syllable. Italicized endings combine two symbols rather than having their own unique one.

| 1–M | 2–M | 1–S/I | 2–S/I | 3M.P –M | 3M.O/F –M | 3M.P/O/F–S/I, 3S–M | 3I–M/S/I, 3S–S/I | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| future (indicative) | sun | sa | set | su | se | sin | sʊ | sʊt |

| present (indicative) | un | ya | et | yeu | e | in | o | ʊt |

| past (indicative) | an | atsa | atsu | ai | ats | atsʊt | ||

| future possible/ unknown | ^sun | ^sa | ^su | ^se | ^sʊ | ^sʊt | ||

| present possible/ unknown | ūn | yā | ū | ē | ^ | ʊ̄t | ||

| past possible/ unknown | ātsa | ātsu | ātse | āts | ātsʊt | |||

| future counterfactual | _sa | _sau | _sai | _sʊ | _sat | |||

| present counterfactual | _(m)a | _(m)u | _(m)e | _ | _(m)ʊt | |||

| past counterfactual | (a̱)mya | (a̱)tsam | (a̱)tsamʊt | |||||

Suffixes:

Verb endings

‘in’ drops the i if verb ends in i or ʊ; ‘un’ drops the u if verb ends in u or ʊ.

| Suffix | Symbol(s) (*flipped) |

| _ | o̱ukka |

| _(m)a | ma̱ntul |

| _(m)e | le̱ |

| _(m)u | vʊ̱yuk |

| _(m)ʊt | mʊ̱tti |

| _sa | hʊ̱la |

| _sai | tʊ̱pait |

| _sat | no̱stop |

| _sau | so̱tu |

| _sʊ | lʊ̱q |

| (a̱)tsam | va̱ |

| ^ | ōcha |

| ^sa | qōka |

| ^se | qāzes |

| ^su | hūqle |

| ^sun | mūnlyu |

| ^sʊ | nʊ̄ma |

| ^sʊt | kʊ̄ho |

| ai | āttal* |

| (a̱)mya | hiqʊ̱mya |

| an | nāng* |

| āts | tsēts |

| ats | tsa̱k* |

| ātsa | lātsek* |

| atsa | tsa̱k |

| ātsu | vūtsu |

| atsu | tsu̱ |

| ē | mē |

| e | e̱s |

| et | tte̱s* |

| in | nīqu* |

| o | o̱ttu |

| sa | sāttekke |

| se | se̱le |

| set | mi̱t |

| sin | pi̱a |

| su | sūt |

| sun | nūpsu |

| sʊ | sʊ̱ |

| sʊt | tsʊ̄ |

| ū | nīqu |

| ūn | tūn* |

| un | nūpsu* |

| ʊ̄t | qʊ̄k |

| ʊt | tʊ̱pait* |

| yā | nāng |

| ya | āttal |

| yeu | vʊ̱yuk* |

| āts-e | tsēts-es |

| āts-ʊt | tsēts-tʊ̱pait* |

| ats-ʊt | tsa̱k*-tʊ̱pait* |

| (a̱)tsam-ʊt | va̱-tʊ̱pait* |

Suffixes:

Other

‘iha’, ‘isi’, and ‘ive’ (habitual) drop the i if word ends in i or ʊ. ‘iu’, ‘i’, and ‘ive’ (with) add v if word ends in i or ʊ.

| Suffix | Meaning | PoS | Symbol (*flipped) |

| (a)chu | become / change to / start | v | tsu̱* |

| (a)f | mis-, badly | (i) | sāttekke* |

| (a)ha | superlative (-est) | (i) | pa̱r |

| (a)m | heard reported (inflectional) | (i) | ma̱ntul* |

| (a)ti | -ward | a | tīhom |

| (a)tte | -less, lack | v | tte̱s |

| (i)ha | over | a | hō |

| (i)si | diminutive | (i) | zi̱ts* |

| (i)ve | habitual | v | vētyan |

| (v)iu | reflexive | v | vīo |

| (v)i | accusative (inflectional) | n(i) | īx |

| (v)ive | using, via | a | vīo* |

| au | locative (at) | a | va̱* |

| ekko | be capable (subj, not obj) | v | po̱ |

| e̱l | imperative – used (very) familiarly | v | le̱* |

| ezi | before | a | zi̱ts |

| hel | beyond/after | a | hēɫ |

| kas | on | a | kāt |

| kaski | onto | a | kāt* |

| kem | comparative (-er) | (i) | ke̱hh |

| ki | dative (to/till) | a | kīti |

| kou | ablative (away from) | a | kko̱ |

| ku | perceived directly (inflectional) | (i) | kūzan |

| long | near/like, -ish, loosely/ figuratively (inflectional) | (i) | lōta |

| lu | under | a | lu̱ko |

| luki | (to) under | a | lu̱ko* |

| lya | augmentative (inflectional) | (i) | lātsek |

| mo | for now | i | mōz |

| ne | vocative (~interjection) | (~) | nēkka |

| nye | off | a | pu̱nye |

| nyeki | (to) off | a | pu̱nye* |

| (o)hh | reciprocal | v | hō* |

| oi | out | a | o̱ttu* |

| oiki | (to) out | a | pʊ̄voi |

| (o)ski | deduced (inflectional) | (i) | vō |

| pei | action, nounifies a verb | n | pēlye |

| taia | be -ful, with, have (m/s (see uma)) | v | ta̱mna |

| tak | in | a | ha̱k |

| takki | into | a | ha̱k* |

| toif | assumed as prior (inflectional) | (i) | tō |

| tu | plural (inflectional) | (i) | tūn |

| u | genitive (be of) (possessive) | v | ūlyus |

| (u)li | far/different from (inflectional) | (i) | līm |

| (u)ma | be -ful, with, have (i (see taia)) | v | mūnlyu* |

| uqu | tend/incline (inflectional) | (i) | qūqu |

| ʊ | group/set | n | ʊ̄s |

| xo | not yet | (i) | xōs |

| yax | from/since | a | tsīx |

History

(Or a slightly more detailed history.)

As I developed the writing system, it brought along with it a history of in-world evolution, as Tesyāmpa’s speakers became more and more literate.

The spoken language did change somewhat during this same period – /l/ and /ɫ/ diverged; /v/ and /w/ merged; /qq/ dropped out entirely; /h/ and /hh/ diverged; /s/ and /z/ diverged; /a/ shifted from aw to ah and /o/ took on the aw sound. Only two of these changes are really relevant to the writing system: vowels tended to drop (CVC syllables becoming more common) so that base words longer than 2 syllables were rare; and when /a/ shifted its sound, the already-established qa syllable stuck around but became pronounced as a duplicate of /ka/.

Written Tesyāmpa

Words in *asterisks* mean the picture or symbol of that word.

Early stage, 1:

Pictograms started to be repurposed, with a lot of ambiguity all over the place. A picture of a pig (*pig*) could either be read semantically to mean pig (kutofi), or be read as a phonetic symbol (P). *star* either meant star (asem) or was read as a P. The combination *pig**star* could phonetically be read as anything from kua to kutofas to kutsem, but it could also be kul, meaning ‘be distant’ (the meaning from *star*, the sound from *pig*), or even possibly esexoq, meaning ‘be stubborn’ (the meaning from *pig*, the sound from *star*). *pig**star**house* might be kkuse, meaning build.

Writing order varied: in a line down, sometimes a line across, sometimes a block. The position and sometimes number of the semantic symbol varied too.

Any pictogram might be used as a semantic determinative (S). The same was true for phonetic symbols, which were drawn pretty freely from the pool of Ss, but there started to be some consistency in which ones were common.

Later, 2:

Longer Ps were assumed to shorten, so that *pig* was ku(t). There was still lots of variation, but consonant (C) grouping was widespread, and fairly consistent in which Cs were grouped: /p/ with /pp/, /n/ with /ny/ and /ng/, etc. (There was an exception in /v/, which was sometimes grouped with /w/ and sometimes with /s/ and /f/, but /v/ was disappearing around this time anyway.) Cs within a group were typically not specified, and so the Ps settled into a pretty standard inventory of only around ~108. There were many more Ss than that. Spaces were sometimes present between words. Affixes were sometimes added for clarification, using Ps.

Later, 3:

One determinative (S) per word, consistently set to the side; Ss were commonly drawn larger than Ps, which had become simplified. If one P symbol was considered clear enough, a second one (or more) was purely optional.

A lot of consolidation happened. Ss had consolidated to about ~96, mostly by doubling up meanings on the same category. Ps were cut down and switched around till there were ~72 symbols, with only a few outliers inconsistently used. *pig* (for example) spread to solidly cover ku(C), not just ku(t). Also, Ps began to be flipped to indicate their reverse reading; flipping *pig* changed it from ‘ku’ to ‘uk’. These flipped symbols were essentially optional and used according to individual discretion.

Suffixes were fairly common, and were tending toward one symbol per suffix, often with a slightly different pronunciation from the corresponding P.

Later, 4:

The meaning of flipped symbols was fairly regular, with some fuzziness around diphthongs and syllable-final consonants.

Words were separated by spaces and usually formatted in blocks, with a couple other arrangements in use. Ps and Ss were both simplified, and only differentiated by placement, not drawing style. The inclusion of suffixes was typical, and they were settling into pronunciations that were unique, one symbol per suffix, with flipped symbols providing more options.

There were still about ~72 Ps, with only a few outliers inconsistently used; most of them doubled as suffixes. At this point, almost all common Ss were those that doubled as Ps, but there were ~16 ‘extra’ ones that stuck around, such as sīn (field) and pʊ̱te (heart).

Current, 5:

Standardization occurred.

Character format:

P (P)

S (suffix)

Pure Ps are still somewhat ambiguous; the S clarifies which word they refer to. With the S, no ambiguity! (Ideally.)

72 is now the standardized number of (unflipped) symbols.

Modern Writing System

Tesyāmpa is written with a logosyllabary consisting of 72 basic symbols, which evolved along with the language (as opposed to being adapted from a different language). Tesyāmpa has only the one writing system, and its speakers have had minimal contact with other languages. Because there’s nothing salient to contrast it to, the script itself has no name other than ‘tīhom’ (writing), much as ‘Tesyāmpa’ simply means ‘language’. Each symbol is written with a single stroke. (The font is a work in progress; when written by hand, there are more ligatures and connections within characters.)

Although each symbol has a maximum of three possible readings, they don’t quite match up 1-to-1. There are actually 70 unflipped phonetic (P) symbols, because the syllables qe and qi don’t exist; including flipped, the total is 136 (with iv, uv, ʊv, and flipped ʊ unused). There are exactly 72 unflipped semantic (S) symbols, including all the Ps plus two additional; flipping has been applied to extend that to 78 categories, into which all words are sorted. Suffixes have been assigned to these symbols, even where the pronunciation could not be closely matched; they make use of all 72 symbols (including the two extra Ss) plus 24 flipped, for a total of 96 standard suffixes. Characters are formed by up to four symbols (one or two Ps, one S, zero or one suffix). Words are composed of one character (sometimes two if a compound), sometimes plus additional suffixes. Punctuation in Tesyāmpa’s orthography is very minimal; the main symbols are just a pause and a longer pause, roughly equivalent to a comma and period.

Flipping

For most symbols, flipping means mirroring them upside down; for those that are symmetrical such that this would produce no difference, they mirror right-left instead. The two extra Ss, ōcha and o̱ukka, have no need to flip. There’s a special case in ‘vʊ’, which (simply being a circle) looks the same no matter how it’s mirrored; instead, since it comes from vʊ̱yuk, meaning shield, it flips ‘over’ so that the straps on the back of the ‘shield’ are visible:

A typical consonant-vowel symbol, when flipped, goes from CV to VC. Since syllables can’t end in a /v/ (and there are no other consonants grouped with it), av/ev/ov instead become au/eu/ou, and iv/uv/ʊv aren’t used. For single vowels, a/e/o become ai/ei/oi; a flipped i or u indicates a new syllable (rather than a diphthong, as indicated by the unflipped symbol). Flipped ʊ is unused.

The six flipped determinatives have a meaning that’s roughly a diminutive of the unflipped version.

Syllables

The first P of a word only flips if doing so fully represents the first syllable (although diphthongs can be unspecified). Cs fall at the beginning of syllables whenever possible: so, for example, a VCVC word breaks into V-CVC and is represented with unflipped Ps as V-CV.

The second P of a word only flips for the same reason as the first P, or if it finishes specifying a one-syllable word (by means of diphthong and/or ending C). A VC that repeats the previous V is read as just its C, the identical Vs being redundant; iC or uC always form a diphthong when applicable, as do unflipped i and u. Otherwise, a second P adds a second syllable, which can leave the first syllable not fully specified. (If the rare base word is more than two syllables, the extra syllable(s) are not represented.)

Examples:

So(y)em or zoi(y)em or fou(y)em are all ‘spelled’ so-em.

Fom is spelled so-om; foyom or zoi(y)om or sou(y)om are spelled so-o.

Soum is spelled so-um; zoi(y)um or foyum are spelled so-u(flipped); zou(y)im or soyim are spelled so-i(flipped).

Determinatives

The determinatives do quite a lot of work. They disambiguate which C of a consonant group is meant (or the equivalent presence/absence of y before a V), whether syllable-final Cs are included and which ones, any unspecified diphthongs, word tone, and any (rare) extra syllables. Determinatives themselves are not pronounced, only written. Exactly one determinative is considered correct for each word; the only exception is the handful of base adverbs that can function as conjunctions, in which usage they’re written with no determinative.

Suffixes

When used for suffixes, each of the 72 basic symbols represents one or two syllables (up to three if an a is added for pronunciation; symbols are morphemic rather than phonemic). The pronunciations are close to their equivalent P (identical where possible), but very irregular; often they take into account the full pronunciation of the corresponding S. The first suffix fills the fourth symbol spot; any additional suffixes combine into (an) additional block(s) and follow the base word, before a space. These additional blocks can have up to four symbols, but all of them are suffixes. They might only be distinguished from compounds by context.

Spelling

A word can be spelled out loud by simply pronouncing the symbols as their corresponding Ps, left-right top-down, including a null if the second P is absent. A flipped [V] is pronounced [V]yu; a flipped v[V] is pronounced [V]vu. (The two extra Ss are referred to by their meaning, ōcha or o̱ukka).

As an example, here’s the spelled-out version of Oldtale:

ho-a-tsʊ-am|tse-ti-mʊ

tso-to-me-ha a-li-e ka-am-ha-ayu la-tse-la he-tsa-pi-avu – pi-a-pi – tu-un-tu.

ho-su-pʊ-ats-ʊt a-la-le-tu la-tse-la-avu va-te-nʊ-ivu – ta-u – tsʊ-la-i-ta|ats-ʊt va-te-nʊ he-i-hi. te-i-kʊ-in hu-qa-tsu ka-am-ha-pe.

te-i-kʊ-ats-ʊt le-lo-su a-la-le-tu le-hi-mʊ-o o-tu-mi la-tse-la, to-zun-lu-ayu va-u-si a-ve-tsu-sʊ he-ko-me tso-ol-ovu-ha.

he-ko-me tso-ni-ivu-ta|e la-tse-la.

And compared to its direct transliteration:

rōamtse̱ti

tso̱ttotak yāuli kka̱mai lātsek re̱itsalau – pi̱a – tūn.

hōifuatsʊt āulyasʊstu lātsekau va̱kteive – tau – chʊ̱lataiayatsʊt va̱kte re̱i. te̱in hūqa kka̱mpei.

te̱iatsʊt le̱lo āulyasʊstu le̱uhio o̱utum lātsek, tto̱ai vāu a̱rvesasʊ re̱ikkoi tsōɫtak.

re̱ikkoi xōinitaiaye lātsek.

(Now that literacy is ubiquitous among Tesyāmpa speakers, there exists slang that pronounces some words as spelled (resulting in a reduced number of phonemes, slightly longer words on average, and a purely phonetic writing system). Who knows how this might develop in the future?)

Kāx

Te̱iʊt nyō-yei vōu.

Rʊ̄ntuiveun ha̱ts yēn sēizahux yaits xu̱me re̱i,

āikaun ālyamive rʊrʊ̄nsʊ sʊ̄let hēɫ a̱umau,

tau, nyōʊt lu̱kolur yaits sāioʊt, tʊ̄fʊt, hōiʊt to̱sive,

hōiʊt re̱ikkoi to̱sive.

Vāue kkēulise kīkati kēsutu pi̱a,

pīlati ye̱r ētuasalyami vūlu hoilʊsē o̱xti a̱umive,

tau, ttāikko-neusin kēpotu li̱vapeiau zālau,

tso̱ttoyax yāuliʊt u̱toskio.

Ēxye āmpakkaie tō, āmpaye kēsutu,

ppāisute vāits e̱imouttekuʊt yāits nūkkettein kēpotu,

āmpain, ēxye pāiʊt kōisau ku̱m ōɫʊt,

vōuʊt, lyāstaheɫʊt.

Zīkatsʊt xēxu-yēi-vēz xūn, āmpaye kēsutu,

xēxalyalongu-yēi, te̱iyeu le̱lo.

o̱uso hūqain fāulyu yāits kke̱nuo a̱um,

kke̱nuo, kke̱nuo.

Qo̱isune ppālau ko̱meʊ yāppuo,

yʊ̱ɫchue le̱ntʊftak li le̱naumtak,

tōkoihel xāhel kka̱ ppūltaiayʊt,

lyānyechuʊt nāng.

Su̱xachuo hēɫ kōnyeo chu̱puʊt a̱um tsōɫisiau,

ālyamun xēi yēn metu nyō-yeiatsʊt vōu,

tau, tōkoi kkēuliun kīkati pi̱a,

yʊ̄zoɫun kē-tezau,

te̱iet hākkoi ye̱f.

Winter

Doesn’t come-already spring.

Make-repeatedly burn we torches while night all,

request-we sing-via might.make.will melt sun snow,

but, comes dawn while is.dim, is.grey, gives cold,

gives always cold.

Want climb-will ascend-ward they.some mountain,

to kill worm-great-rumored ice-of exhale-might downward snow,

but, call they.others foolish-act that,

ago far is.dead-must.be.

How explain this, say they.some,

nod.at land is.bleak-plain.to.see while are.contemptuous they.others,

say, how pertains.to year four are.previous,

are.spring, are.sunshiney.

Maybe.was sleep-is.of-already-just-might it, say they.some,

sleep-great-like-is.of-already-might, don’t-you know.

Like.this continue-they argue while falls snow,

falls, falls.

Ends.up venture.out adult-group is.few,

vanish grey-in and white-in,

when-after day-after one fret.wait-has,

clear-become sky.

Causing-becomes sun honored transform.to snow river-small,

sing be.grateful we because.of come-already-did spring,

but, when climb-we ascend-ward mountain,

search.for them-honored,

don’t-we find nothing.

A note

Tesyāmpa speakers mostly don’t live in places with much snow, but some of them have spread into colder mountainous territory where the winters are longer and harsher, and where this poem could be set. There have not, however, been any definitely verified sightings of an ice worm.

The original poem

Winter

Spring hasn’t come.

We burn torches all through the nights,

and sing for the sun to melt the snow,

but dawn comes dim and gray and cold,

always cold.

Some want to climb the mountain,

to kill the ice worm that breathes down snow,

but others call that folly –

it’s long since dead.

How do you explain this? some ask,

nodding at the bleak land while others scoff,

and what of the last four years?

spring and sunshine.

Could be it’s just been asleep, some say,

sort of hibernating, you don’t know –

and on they argue while the snow falls,

falls and falls.

In the end a small group goes out,

vanishing in the gray and the white,

and after one day of waiting,

the skies clear.

The sun starts turning snow to streams,

and we sing thanks that spring has come,

but when we climb the mountain,

searching for them,

we find nothing.